Noblesse Oblige

A Christmas Special

By:

Pete Bruno

(© 2013 by the author)

The author retains all rights. No reproductions are allowed without the author's

consent. Comments are appreciated at...

“That’s torn it,” said Mr Chilvers. The dignified retainer was doing the bedroom at Croome that was shared by his lordship, the Marquess of Branksome and his lover, Stephen Knight-Poole, who had been adopted as the ward of his late brother. The unconventional sleeping arrangements required the utmost discretion, and so it was that Chilvers himself chose to attend upon the personal needs of the boys when they were down at the country house that was the ancestral seat of the Pooles.

The sheet had torn and Carlo Sifridi, the equally discreet valet from the London house, came over to the bed when he heard the sound of the rent linen.

“It was adhered to the mattress, Carlo,” observed Chilvers, holding up the ruined sheet, “I will have to get fresh sheets from the linen room.”

“That would be Mr Stephen, Mr Chilvers,” said Carlo examining the tragedy. Chilvers nodded. “He’s awfully hard on the Manchester, ain't he? I have some fearful messes to clear up at home and I find it everywhere. There was this one time I found it had all run down the leg of the billiard…”

“I think that’s enough, Carlo,” interrupted Chilvers, “It’s not our place to comment on our betters. It is enough that Mr Stephen keeps his lordship happy.”

“Oh he does that, Mr Chilvers, and I never complain about having to clean up too much happiness, although his lordship usually likes to…”

“Carlo, that’s enough! Come and help me go over their evening clothes; I think Mr Stephen needs a bigger size in collars. I have noticed he has gained a lot of muscle over the last six months.

Stephen and Martin had come down to Croome for Christmas. Martin had completed just a term at Pembroke College at Cambridge and Stephen was in the middle of his Engineering degree at the University of London. War had been declared in the previous August, but instead of the whole thing being over by Christmas, it appeared that it was only just the beginning and the boys had found that the students and the younger dons were starting to seep away from their institutions and that the whole country was a different place to what it had been in the days of peace, which now seemed strangely distant.

It was snowing steadily as Carlo helped them undress. Martin looked out of the bedroom window into the velvet blackness against which the tumbling white feathers stood out, reflecting the light from the house.

“It’s going to be a proper Christmas,” he said. “This is how I remember it as a little boy; we always had plenty of snow in the week before and it was warmer in the summers too. I don’t know what’s happened to the weather; we don’t have snow in winter and the summers are just cool and wet.”

“Well, this year you can’t say that, Mala,” said Stephen who had thrown his shirt aside and came up barefooted behind Martin in just his evening trousers with his braces attractively subdividing his naked shoulder blades and chest. He put his arms around Martin and rested his chin on Martin’s shoulder and gazed out the window. Martin pushed back and felt Stephen’s cock hanging recklessly beneath the Barathea cloth. He positioned himself so that the crack in his buttocks was pleasantly aligned with it.

Carlo was hopping about the room picking up discarded clothes and searching for a collar stud that had rolled under a table.

“I’m sorry, Carlo, it just popped out,” said Stephen when he noticed the valet down on all fours.

“I wouldn’t stay like that for too long, Carlo,” said Martin, turning sideways. “Not unless you’re looking for the village stud, rather than the one from his collar.”

“Mr Chilvers was just saying that you might be needing a bigger size, sir— in collars that is.”

Martin turned around and kissed Stephen’s throat. “Have you been doing exercises Derbs?”

“Yes, an hour every morning with the weights before it’s light and then I go to ride in Rotten Row before breakfast. I’m hungry by then, I can tell you.”

Carlo fetched the tape measure from the dressing room and he and Martin tried to find the size of Stephen’s neck. “It’s not too thick is it Mala?” asked Stephen.

“No Derbs, it looks just fine.”

“Do stop talking, sir. Your Adam’s apple is bobbing up and down and I can’t hold the tape. Perhaps if you sit down.”

Stephen sat in a chair and lifted his chin. “Perhaps if you were to sit on his lap, Carlo?” suggested Martin.

Stephen put his knees together and Carlo spread his own and straddled the beefy lad’s thighs. Stephen winked at Martin and seized Carlo tightly about the waist. He then wriggled his groin under Carlo who tingled. “You’re not wearing any drawers are you Carlo?”

“Of course not, sir; 16 and-a-half I think.”

“Let’s measure his chest, Carlo,” said Martin who was rubbing his hand across it.

“Oh Mr Chilvers and I already have that measurement,” said Carlo who was still pinned tight and making no moves to escape. He too ran an appreciative palm over Stephen’s chest and then leaned in and kissed the small chevron of black hair that formed an ornament to Stephen’s sternum. Stephen, loving the attention, released his embrace, stretched luxuriantly and clasped his hands behind his head. The heady scent of his sweaty armpits filled their nostrils and Carlo and Martin took one each. When they came up for air, Stephen was grinning arrogantly. Martin and Carlo looked at each other and in unison stretched the elastic of Stephen’s braces back like long bows and released them with a resounding snap as they struck Stephen’s big, brown nipples.

“Ow!” he cried indignantly and the pair took pity on him for their cruelty and soothed the flesh with their tongues.

“Let’s measure him and see how much of a man he really is, Carlo,” suggested Martin, excitedly. “I’ll get him hard and you be ready with the tape.” Carlo thought this was a rather feudal division of labour, but complied. Stephen’s braces were slipped aside and his trousers were removed and he stood there in his naked magnificence. Martin set to work and Carlo assisted where he could and made helpful suggestions. “I think he’s ready now, Carlo, said Martin, wiping his mouth. Carlo let go of Stephen’s balls and removed his index finger and reached for the tape. Just as he placed the measuring device on Stephen’s impressive manhood everything went black.

“Oh no, it’s the generator again, isn’t it Carlo?” said Martin’s voice in the dark.

There was no reply from the valet, only a sort of gurgling noise and the sound of Stephen panting. This went on for some minutes and then the lights came back on for a just a few seconds before guttering and giving out again. In that moment, it was enough for Martin to see that Carlo had Stephen’s seed all over his face and was operating his tongue in an endeavour to savour it. Stephen wore the appearance of one of Mrs Tidpit’s milkers just returning to pasture and then Carlo looked up at Martin with the same expression that Job affected when he had ‘rolled in something’.

With the fire in the bedroom stoked and making lovely patterns on the Jacobean plasterwork of the ceiling, Martin and Stephen lay on the floor, wrapped in just some blankets they had pulled from the old canopied bed. Martin had wanted to watch the snow out of the low window and they lay naked on their stomachs with their heads in their hands. Martin was in a world of the senses: there was the coarse wool of the blanket on his skin and the smooth satin binding of its edge; there was the texture of Stephen’s skin—smooth and firm on his body but dusted with hair on his legs and buttocks; there was the chill of the night air but the warmth of the fire and the warmth of the fire of his lover, for Stephen was never cold and better than any hot water bottle. He felt deliciously safe with Stephen; that was a lovely feeling too.

“How did you learn to fuck like that, Derbs?” said Martin as he felt Stephen’s seed begin to trickle down his leg—another thing to add to his catalogue of the senses.

“Should you be using coarse language like that, Mala?” asked Stephen facetiously.

“Well I don’t want to say ‘making love’ like some lady novelist. You were fucking me, I’m quite certain of that and I’m sure it’s a good old Dorset word. I should ask Douglas Owens.”

“I don’t know. I just do it, I suppose. I think about it a lot. I hope you don’t think that’s perverted. I did have a little bit of practice before I met you, all those years ago.”

“Five and-a-half. Yes, you told me. Elsie and some other girls and a man asked you to fuck him at The Feathers.”

“That’s right. I was only about 12 or 13 and he got me to carry his box up to his room. I didn’t have much technique then, Mala. When I tried to stick it in he screamed so loud I gave him back his shilling and fled.”

“You could have been with him now, instead of here.”

“I’m sure he had a wife and children somewhere. I’d much rather be your kept boy.”

“Don’t say that, Derbs, not even as a joke. You’re your own man—every last painful inch of you; we’re partners.” Martin was silent for a few minutes and tried to keep his eyes open to look at the snow, but it was an effort. “Derbs?” he said, rolling over onto his back and looking up at Stephen.

“Yes?”

“I wish I could have your baby. Does that sound silly? But I’d really like to give you one.”

“Yes, it does sound queer, I suppose.” He paused for a long time, lost in thought. “But what’s more silly than love? You say it because you love me and want to make me happy—and you do—even without that, but I’m touched all the same. And Mala, you can keep your figure.”

Mr Destrombe laboured through the snow, which was getting deeper. He pulled on the great brass device that rang the bell at Croome. After an eternity Chilvers came.

“Mr Destrombe, sir, what are you doing out in this weather? Come in, sir. Elspeth, fetch a towel and bring some cocoa for the vicar.”

Mr Destrombe was moved to the blazing fire in the Great Hall by the Christmas tree and Mr Chilvers took the liberty of removing the priest’s Wellington boots and gloves and rubbed his hands to restore circulation.

“Your telephone is not working, Chilvers. Is his lordship still up?”

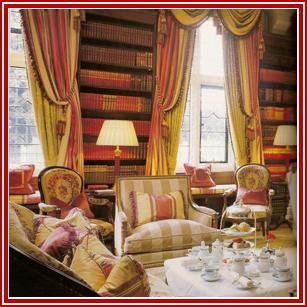

“Yes sir, he is playing cards in the library with Mr Stephen and Lord Alfred. I will call him.”

Martin arrived and Mr Destrombe looked up at him from the fireside. “Do forgive me for calling at this hour your lordship, but it’s one of the Belgian refugees down at the school.”

“What about him, Mr Destrombe?” asked Martin.

“Her, sir. She is with child and it is due quite soon. I don’t think the school is a suitable place for her confinement. Many of the refugees have seasonal illnesses and I would have her at the vicarage, myself, except that my wife has the influenza too.”

“Of course she can come here, Mr Destrombe. Mr Destrombe,” began Martin in a hushed tone, “was the poor girl a victim of some Hun outrage?”

“Oh no your lordship, she has a husband. They are both only 19 and fled after the fall of Liege. She is the niece of General Leman who is being held prisoner and he was a student of chemistry before being called up. He is now in Cheshire trying to secure a position.”

Chilvers and Mrs Capstick were summonsed and sent to prepare a bedroom for their guest. Stephen was brought into the conference and asked how Mme Cuvelier was to be brought to the house through the deep snow.

“I will drive the motor, Derbs,” said Martin. Mrs Capstick can come with me and help Mme Cuvelier.”

“But the motor will be snowbound too, Mala. I had better come and bring some shovels.”

So they set off, with Mr Destrombe a passenger on the outward trip so that he might return to his wife. Mrs Capstick had a number of blankets and hot water bottles on-board and a fire had been lit in the room the young lady would occupy.

Martin was at the wheel in the absence of Jackman who had joined up in November and they set off for what would normally be a short journey. The headlamps picked out enough familiar landmarks to tell Martin he was still on the drive, but just before they got to the elm avenue there was a bank of snow where the wind had drifted it. Stephen leapt out with a shovel and cleared it enough for Martin to push through. They pressed on under the elms whose boughs were bent low. At the little bridge the tyres slipped on the ice and a collision was narrowly averted. Once more Stephen had to get out and clear the path but finally they reached the building for the new higher elementary school, which had yet to see a pupil.

The would-be school presented an unusual picture: rooms containing the usual blackboards and daises that remained unused, now had sheets and blankets draped over the internal windows to transform the classrooms into cosy family apartments with beds, tables and chairs and even Christmas trees for the twelve Belgian families who now called it home. The kitchens, where girls were to learn the arts of homemaking, were now real kitchens where the refugees were sharing a very delicious smelling stew. The whole place was wonderfully warm due to the efficient central heating apparatus in the basement that Marin was now glad he insisted be included in this building that he was very much the author of.

In one of the rooms was Mme Cuvelier who was smiling with embarrassment and had her pretty little hands placed apologetically on her swollen belly. Mme Cuvelier was a very attractive young lady with dark hair and lively blue eyes. She had a few words of English but they managed with a combination of French and English to understand that she was most grateful for his lordship’s generosity and that she feared the influenza, which had killed her mother some years previously. She was made to understand that Martin and Stephen were only too pleased to have Mme and M. Cuvelier as their guests. Martin paid tribute to her gallant uncle, the General, who was captured unconscious by the Germans in the ruins of his fort and allowed to keep his sword. She gave a little bow at the compliment, but laughed when she found she could not bend.

Well wrapped up, she managed to waddle to the Rolls Royce, calling farewell to her fellow refugees. Mrs Capstick made a pleasant fuss and Mme Cuvelier complained that she was now too warm and so one of the bottles was removed. She had a small suitcase, the larger one being left until later. Mr Destrombe made for his own hearth, which was not far away.

The motor set off at a crawl, retracing its path. Stephen had to get out twice, but his previous path was still mostly clear, that is until they reached the elm avenue. Here the headlamps picked out a large fallen limb, which had brought down a lot more snow with it and completely blocked their path.

Both Stephen and Martin used their strength to move the branch aside and then took up the shovels. Mrs Capstick, in the spirit of the new age, herself took to the wheel, having taken lessons from Jackman, and nosed the Rolls Royce forward into the path the boys made before it in the direction of a bright star which was the light from an uncurtained upstairs window in the house.

Thus they proceeded, Mrs Capstick at the wheel and Stephen and Martin sitting either side of Mme Cuvelier to keep her warm until they came to the very end of the avenue where the wind and snow had brought down more branches and the snow was banked up very high.

“It’s no use, Mala. We’ll never get the motor through here. It’s not far to the house now if we cut straight across the lawn rather than drive around the perimeter. I’ll carry Mme Cuvelier. Even with the baby she doesn’t seem that heavy.”

As there was no better suggestion, Mrs Capstick covered Mrs Cuvelier completely with a blanket and Stephen took off his jacket and, just in his shirtsleeves, swept her into his arms and set out across the snowy lawn in the direction of the cheery lights of the house—a distance of about a thousand yards.

“Are you all right?” Mrs Capstick kept repeating.

“I’m all right, Mrs Capstick,” replied Stephen, huffing.

“Not you, Mr Stephen! I was asking Mrs Cuvelier,” she replied in mock indignation.

Stephen was puffing but kept making silly jokes to Mme Cuvelier. Muffled sounds and some giggles came from beneath the shroud.

“Watch out for the pond, Derby!” called Martin who was carrying the suitcase when they neared the centre of the lawn.

Finally the crunch of gravel beneath the snow showed them that they were on the drive and it was only a few feet to the door. Martin ran ahead and pulled the bell, with urgency. There was a great barking and delighted yelping from the dogs and Mme Cuvelier was deposited in the Great Hall by the Christmas tree and unwrapped. She was in good condition and her cheeks were flushed. A chair was brought for her and she lowered herself into it and Martin put her feet on a stool. They were regarding her intently to see if she was unharmed. She looked up at the three of them, thanked them and gave a pretty smile. The dogs came and sat down by her.

Stephen was out of breath and sweating. He pulled off his soaked shirt and Chilvers wrapped a blanket around him and rubbed him to dry him off. Mrs Capstick did some more fussing around Mme Cuvelier who did not seem to have suffered in her trek and showed the evident spirit of the late Captain Scott or perhaps her uncle the gallant general. A maid, Elspeth, was assigned to the visitor and Martin, cold and wet himself, turned Stephen in the direction of the stairs. Mrs Capstick came after them. “You’re a good boy,” she said quietly to Stephen and kissed him on the cheek.

“What about me?” cried Martin.

“You’re an angel,” she said and dared to give him a kiss. “I wish your mother was here to have seen you.” She turned and went back to Mme Cuvelier while Martin and Stephen, bemused, continued up to their room.

“It’s a hot bath for both of you,” said Chilvers. “Separate or together?”

“ Chilvers!” said Martin. “What a suggestion! Together, of course and send in Carlo.”

When the boys were dressed again they went to Mme Cuvelier’s room, which was guarded by the dogs who had followed her up. There was light under the door and they knocked gently. Elspeth opened the door and bobbed. “Madam is sitting up in bed, your lordship; she is receiving visitors.”

The boys entered and saw the young lady was propped on pillows, looking quite well under many layers of wool, silk and satin. She looked too young to be having a baby, but obviously wasn’t. They bade her a good night and withdrew to their own room. Within minutes their warm clothes were shed and they were under the covers of their own bed where, once again, Stephen was terribly hard on the Manchester.

The next day was Christmas Eve and Martin wondered if their guests would be able to make the journey through the snow. It had stopped falling by mid-morning and a party of workmen from the estate dug out the Rolls Royce and cleared away the fallen branches in the avenue. The Plunger with his valet and Christopher Tennant were arrivals by the morning train and Aunt Maude, Sophia and Anthony came on the later one. Lord and Lady Delvees arrived in a phaeton just as the snow started to fall heavily again around 4 o’clock when it was already quite dark. The telephone was still not working but the boy from the post office managed to get to the house with a telegram. It was from Donald Selby-Keam. He would not arrive until Boxing Day.

The hall was a pleasant confusion of cases and trunks, which more than anything symbolised the festive season at Croome to Martin. The Plunger was busy showing them an expensive new rifle he had brought should they do any shooting and he had designed an entirely new set of hunting pinks for New Year’s Day which he was anxious to show to the fox and horses. There were only three footmen and soon to be just two as the young men joined up and they were kept busy ferrying the luggage up to the guests’ rooms where their things would be carefully unpacked from their tissue paper and brushed, ironed and neatly hung and shelved, with toiletries set out and evening clothes laid ready on their owners’ beds.

Tea was a jolly meal with a variety of special pastries and smoked salmon sandwiches done in Cook’s unique manner and served in the Spanish room, which was the lightest at this time of the year. Lord Delvees asked all the young ones about their studies, including Antony who was up at Oxford still and The Plunger who was at the Slade School in London. Aunt Maude and Sophia talked of the coming ‘season’ and what the War would mean. “If there is no season, how will our girls find husbands?” she lamented.

“Perhaps I could borrow Mr Craigth’s new rifle and bag my own, Mother,” said Sophia who was rather weary of the social scene and had begun to think that her friend, the former Miss Orchard-Baird, had done the right thing in finding an American of mature years to free her from London life.

The carol singers could not get to the house through the snow this year, so in the drawing room, when the gentlemen had joined the ladies, Sophia and her mother played and the house party had to make do with their own voices. Aunt Maude thumped away at the Broadwood, which would surely have to be tuned in the New Year while the others sang out heartily:

“…Jesus our Emmanu-el

Hark the herald angels sing

Glory to the new born King.”

It was time for supper and to light the tree in the Great Hall. The guests trooped out and were joined by the servants for the ceremony and Martin had his speech prepared. He was just going over his notes and had noticed that the toast read ‘to H.M. King Edward’ which he thought wasn’t quite right, when there was a shout from Elspeth: “Mrs Capstick! She’s begun!”

The girl came clattering down the stairs and rushed up to the housekeeper who looked alarmed. “But she said she wasn’t due for a fortnight,” said Mrs Capstick in distress to the audience at large. She headed for the stairs.

The speech with its antique reference was quickly forgotten and Martin went to his aunt to ask what to do. “You should telephone for the midwife and the doctor, Martin.”

“The instrument isn’t working but I’ll send someone to Dr Markby’s. Mrs Tibbs lives in Lesser Branksome; we’ll never get to her in time, although it takes a long time for the baby to actually come, doesn’t it Aunt?”

“I wouldn’t know I had gas for my two, but I think it does. Where is her husband?”

“In Cheshire looking for a job. I don’t even know where to send for him.”

“Mrs Capstick will know about babies, Martin,” said Stephen.

“Don’t be silly, Derbs. After all these years, surely you know there was no Mr Capstick? ‘Missus’ is a courtesy title given to all cooks and housekeepers. Lady Delvees, do you know about babies?”

The Viscountess drew herself up as if she had been asked about necromancy or coining or some other suspect activity and Martin realised she was not going to be of much use either.

“Derbs, you’ve delivered foals and calves…” All eyes turned to Stephen.

“Yes, and puppies, kittens, otters, and blackbirds—but not babies, Mala; we will just have to wait for Dr Markby.”

“I remember our old nurse cutting up sheets,” said Lady Delvees. “That was during the Crimean War I recall.” Miss Prims left the room to search out old sheets.

“And boiling water,” added Aunt Maude, “I read in a novel where they boiled water. What for, I could not possibly say; possibly to give the baby a bath.”

“Or make tea, Maude,” snapped Lady Delvees. “Even I know you mustn’t boil a newborn. They have a tepid wash. Oh I don’t know how I can even talk about such things in front of young men.”

“The boiling water is to sterilize things,” said Christopher. “I’m studying to be a doctor.” All eyes now turned to him. “But we won’t come to babies for a few years yet.” Some eyes wandered.

“Still, you are our best hope, Chris,” said Martin and the eyes fixed on him again. “Of course Dr Markby can take over when he gets here.”

Reports kept coming down to the Great Hall. The more delicate ones were only whispered. Apparently Mme Cuvelier was doing well but had declined the offer of tea and a mince pie.

An hour later Paul the footman returned, but without Dr Markby. “He’s over at Pendleton attending to a case of twins, your lordship. The snow is so thick, I would not rely on him coming before morning.” The exhausted young man was taken to the kitchen and dried off and refreshed with what Mme Cuvelier had so ungratefully refused.

“Babies take a long time to come into the world. It is unlikely to come before morning in any case,” said Aunt Maude with finality.

The guests gradually began to resume their civilian conversations and some Christmas presents were unwrapped. When Chilvers wheeled in refreshments at about 10 o’clock and the party had almost regained its former jollity. By 11:30 most of the guests had retired to their rooms.

Along towards midnight, Elspeth came down the stairs looking agitated. “Oh your lordship, she said, giving a quick bob, “I think it’s really coming now. Please come up, Mrs Capstick needs help.”

“I can’t go up, Derby. I don’t know anything about young ladies. You and Chris go.”

“You’re a man of the world, I dare say, young Knight-Poole,” said Lord Delvees who was dozing by the fire in an armchair with his pipe and a nice glass of old brandy. “You would not be frightened of a woman.”

“Oh yes I would, sir. But I had better go. Come with me Chris.”

The two boys stepped over the sleeping dogs and entered the room to the relief of Mrs Capstick. Stephen explained in French that Christopher was a medical student and the son of a country doctor. He omitted his own veterinary pedigree for fear of alarming the young lady further.

She looked very much like…well, like a young lady having a baby and she shed a few tears and called for her husband when the pain was upon her.

Christopher did not have a stethoscope but took Mme Cuvelier’s pulse and pronounced it satisfactory. He then braced himself and had a look at the business end, trying to affect a professional sang froid he did not quite feel. “She is halfway dilated,” he said and Stephen thought he knew what that meant. He held Mme Cuvelier’s hand and wiped her brow. She squeezed his hand and gave him a tight smile.

There is little modesty in the lying-in room and Stephen was eventually persuaded to look too, Chris requiring a second opinion. “It’s the head that comes out first, not the hooves (BRILLIANT!) isn’t it?” asked Stephen. Chris nodded. “Well I think I can see the head— with black hair and everything.”

Mme Cuvelier caught this and was just about to say her husband had such hair when she was convulsed by a spasm of pain and all three of them cried: “Push!”

And there it was in Stephen’s hands (which had been scrubbed in the hot water) a perfect baby boy— although a little red, bloody and wrinkled if fact was to intrude gauchely over fiction—and with a good set of lungs. He was given a gentle wash (rather than boiled as Aunt Maude would have had it) and checked over by Christopher and placed on his mother’s breast by Stephen. She looked up at Stephen and smiled and then had eyes only for her new baby boy. Chris used sterilised scissors to cut the cord and hoped his father would have been pleased with the knot, for he did not like the sort that protruded. Stephen and Mrs Capstick set about cleaning up which was not pleasant but it had to be done. Mme Cuvelier was very tired but thanked them. The baby was wrapped up in towelling, Mme Cuvelier not having had time to get her few baby clothes together and already Mrs Capstick was planning on whom to ask in the village for such garments. She and Elspeth would take turns in sitting up and if Christmas dinner had to suffer, then so be it. Outside the door Job and Stephen’s border collies were alert and wagging their tails.

Stephen and Christopher returned in triumph to the Great Hall, which was empty save for Martin who was asleep in a chair with a blanket over him. “Wake up Mala. We have a boy, and mother and baby are doing well.”

Christopher and Stephen were grinning as if they had given birth themselves and Martin shook their paws. He walked them up the stairs with his arms about their shoulders. “You know if that baby grows up and lives to be 85 and one week, he will see the next millennium. That sounds fantastic, doesn’t it?” The others agreed that it did.

The next day the boys slept late. Chilvers brought the news that Dr Markby had managed to reach the house at half-past seven and that the mother and baby were doing well. “Thank you Chilvers," said Martin, "and merry Christmas to you.”

“And merry Christmas to you, your lordship and to you too, Mr Stephen.” Stephen didn’t reply for he was still fast asleep and only his broad naked back was presented to the butler. Martin kissed it.

The snow was still thick and compelled everyone to remain indoors, foregoing the Christmas service in the little grey church in the village. Martin found a box with some old photographs and tintypes and was going through them. “This is my mother…this is my father and mother in Switzerland on their wedding tour….” Stephen looked for the family resemblances of which there were many. There was a cabinet portrait of Martin and William when they were about seven and eighteen. There were tintypes of nannies and governesses, long gone. There was his father in the uniform of a colonel in the Earl of Holdenhurst’s Yeomanry. There was an early one of Martin’s father as a baby with his siblings and his parents. That must have been taken in the late 1850s. Another of interest was taken when the Prince of Wales visited in the 1880s or 1890s. They laughed at the strange fashions and curious expressions of yesteryear.

After their big dinner, they gathered in the Great Hall again and Martin was persuaded to read as his mother used to in Christmases past while his guests did not fight hard against temptation and managed to find room for yet another slice of pudding or a mince pie or perhaps just some nuts and a touch more of the mulled wine.

He had

brought Smike out in his arms—poor fellow! a child might

have carried him then—to see the sunset, and, having arranged his

couch, had taken his seat beside it. He had been watching the whole

of the night before, and being greatly fatigued both in mind and

body, gradually fell asleep.

The big Yule log, which had been decorated with holly and hauled to the fireplace by two workmen from a remote corner of the estate, settled in the enormous fireplace with a comfortable sound

He fell into a

light slumber, and waking smiled as before; then,

spoke of beautiful gardens, which he said stretched out before him,

and were filled with figures of men, women, and many children, all

with light upon their faces; then, whispered that it was Eden—and

so died.

It was very late when The Plunger and Christopher joined the boys cosily in Martin’s great bed where they tried not to spill their hot toddies on the sheets when Stephen insisted in inspecting their nakedness closely for signs of change or perhaps only to renew his familiarity. Inevitably they discussed the War. The Plunger had already enlisted, he said, as Stephen ran his nose through his ginger armpits and Christopher too was keen he proclaimed, as he lazily stroked Stephen’s silky cock under the blankets. Martin was not so enthusiastic, but the militia formed by his great-grandfather had been revived and so he had little choice. Then Stephen stretched his big arms and arched his back, squashing the others. His cock slapped against his stomach. “I will decide when I return to University next term,” he said. Already his friend and tutor, Jack Thayer, had been seconded to the Naval dockyard as an engineer and Stephen was trying to imagine himself doing something similar, but it was hard to know what it would be like. Whatever it was like, it would not be as other people were now painting it.

Aunt Maude and her children left on Boxing Day with Aunt Maude saying that she hoped to be able to salvage something of this wartime ‘season’ and that the boys must be certain to come up to London for the ball at Holland House. Christopher was also keen to see Phyllis Dare in ‘The Girl from Utah’ at the Adelphi before he returned north to his parents.

Stephen spent most of the day— St Stephen’s Day—with his father while Martin distributed boxes to the servants and made visits in the village where the depth of the snow permitted. In the evening there was a new crop of dinner guests including Donald Selby-Keam whom Martin had seen quite recently as they were at Pembroke together, and neighbours: the Hore-Grimsbys, the Bonningtons, Miss Francing as well as Mr Destrombe (who had abandoned his wife on the promise of a good dinner) and the Lord Lieutenant of the County and his good lady. Stephen thought this was a dull crowd and was glad The Plunger, Chris and Donald were there and so he was dismayed when, after tea, Martin said that he didn’t feel well and thought he would remain in his room. He looked fine to Stephen but he complained of a headache and Stephen hoped he wasn’t getting influenza. “You will have to host the dinner, Derbs. I’m sorry. I will make it up to you, I promise.”

Thus Stephen found himself at the head of the enormous table in the gloom of the Gothic dining room where one felt one had to shout in conversation. There was also the problem of table manners; it wasn’t that Stephen had not mastered polite behaviour, but it was more from habit that he still looked to Martin for the cue as to which fork to use, especially when there were curious instruments like marrow spoons and melon forks to be manipulated. He still couldn’t quite understand that asparagus was eaten with the fingers, even by well-bred persons.

Chilvers served the soup and Stephen sucked the liquid from the side of the large spoon (the round sort being unknown among the upper classes) trying not to make a noise, although he could hear Sir Bernard Bonnington syphoning from well down the table.

Stephen was making pleasant conversation with Mrs Hore-Grimsby on his left, although she was rather deaf and kept replying ‘yes’ and ‘no’ but not always in the accustomed intervals. “Belgium’s fate has been truly shocking, Mrs Hore-Grimsby,” said Stephen loudly, leaning on one elbow to get closer to the old lady’s ear trumpet.

“No, it was a great success.”

“I mean the German soldiers and all those poor nuns.”

“No, I was there myself. I took my maid and we made 17 pounds although I would have loved a sit down, but I didn’t have a spare moment.”

“You were in a convent, Mrs Hore-Grimsby?” asked Stephen incredulously.

“No, in the Women’s Institute Hall it was.”

“What was?”

“The Belgian fete.”

Stephen was just about to reply, but he couldn’t quite frame the words when he felt something in his groin. It was his fly buttons being probed. He dared not remove his napkin and look down and, for an instant, he looked at Mrs Hore-Grimsby for the guilty party. However, she was just saying to the Lord Lieutenant on her left that Maude’s kitchen maid had most certainly not been appointed Secretary for War and she had both her hands fully occupied with ear trumpet and soupspoon.

He felt his cock being drawn out, so it clearly wasn’t one of the dogs under the table. Then he felt his foreskin being painfully stretched, just as he liked it. “Do you think it will stretch that far?”

“I beg your pardon Sir Bernard?” said Stephen wincing.

“Will this DORA legislation affect the sale of alcohol at private clubs as well as public houses?”

“I really don’t…” Stephen felt a familiar pair of soft lips engulf his cock and he relaxed. “Yes possibly the Kaiser has bitten of more than he can chew by invading Russia, Christopher but…”

The soup was removed and the fish arrived. Chilvers bent to serve and observed that Stephen’s trousers were missing. He raised an eyebrow and Stephen blushed and murmured something about the turbot having firm white, flesh.

There was a lemon sorbet before the roast and Stephen passed the ice under the cloth because he knew it was Martin’s favourite. Martin’s lips left Stephen’s warm, throbbing member for a moment and then returned with icy fury. Stephen gave an involuntary squirm. “What’s the matter, my boy?’ asked Uncle Alfred. “Did someone just walk over your grave?”

“Just a sudden chill, sir; a shiver down…down my spine.”

“Do be careful, Mr Stephen, that’s how Mrs Destrombe ended up in bed,” put in the vicar.

Martin was now taking Stephen to the edge and, through practice, keeping him happily suspended there. This went on all through the remaining courses.

“Martin is missing honey-glazed spatchcock,” said Uncle Alfred. “He likes to bag his own with a small bore.”

Stephen could muster no reply to this as Martin had just moved from licking his muscular thighs to now rolling each of his testicles in his mouth.

The pudding was an elaborate thing with whipped cream so naturally some spoonful’s were passed under the table while the conversation above it turned to the two musical plays of the day, ‘Adele’ and ‘The Girl from Utah’, with Christopher being very informative.

Martin had managed to cover Stephen’s privates in Chantilly cream and Stephen had edged lower in his seat so that Martin might have better access to his buttocks whose pleasant cleavage was now a confection of cream and preserved raspberries that Martin found very tasty indeed.

The conversation swung back to the serious topics of food shortages and the shelling of Hartlepool and Scarborough and Sir Bernard thought it was particularly heartless of young Knight-Poole to be grinning away at the misfortune of his fellow countrymen up in Yorkshire.

Eventually the wife of the Lord Lieutenant caught the ladies’ eyes and they left for the drawing room, Stephen only rising an inch or two from his chair and employing the napkin for modesty. The port was then passed and Mr Destrombe wondered why Stephen would not rise from his seat to move the decanter a few feet, instead calling Chilvers each time it was with him. Martin now had Stephen right down his throat and gagging sounds could be heard. “It’s the wind in that old chimney,” said Lord Alfred. “Some people have thought that the room was haunted by an unquiet spirit.”

Martin was now working on just the tip and he thought that he better finish Stephen off before he burst. He increased his ministrations.

“Will you come for a game of billiards, Stephen?” asked Uncle Alfred, “You owe me a chance at revenge.”

“I won’t come tonight sir…” began Stephen.

Oh yes you will thought Martin under the table and the elderly men left the room just as Stephen’s face contorted, his legs stiffened and his chair scraped backwards on the floor.

“What on earth is the matter?” cried The Plunger when he saw Stephen appearing to have a fit. Uncle Alfred heard this too and was just about to open the door again when Mr Hore-Grimsby asked him something about the Pathan tribesmen and so he walked on.

Martin crawled from his place of concealment, his face and hands covered in cream, fruit and worse. Stephen stood and revealed his lower portions in a similar condition and his seed still oozing from his flaccid member. Christopher, Donald and The Plunger rushed over to assist in his cleaning up, not wanting to waste anything with a war on. Stephen was just put back into his trousers when Chilvers came into the dining room. He looked around and knew the boys were up to no good. His eyebrow was working overtime.

“Your lordship, I thought you were unwell and in your room. Have you had any dinner, sir?”

“Yes thank you, Chilvers, only one course but it was very filling.” They left hurriedly before Chilvers had time to discover the sticky mess by Stephen’s place at the head of the table.

The servants were having their Christmas dinner in the servants’ hall in the evening. Mr Chilvers and Mrs Capstick presided and the most junior skivvies waited upon them in an imitation—or parody—of their betters upstairs. Higgins and Carlo were down from London and there were two lady’s maids who joined them but the main attraction was the Hon. Archibald Craigth’s manservant, ‘Gertie’.

“Well,' I says to this red-faced old major, ‘I’m a conscientious objector.’

“‘On what grounds, Mr Haines?’ he says.

“‘I’m a pacifist,’ sez I.

“He puffs up and says: ‘Are you telling this board that you would not fight to defend your own country?’

“‘No dear,’ sez I, ‘that’s about the size of it.’

“He goes all red and says ‘I’m not dear, I’m an officer in the Coldstream Guards, Mr Haines.’

“‘No, I’m sure you’re not,’ I says ‘but that does look a very expensive uniform.’

“‘Mr Haines, are you married?’ begins another one.

“‘No, I’m an unclaimed treasure,’ I say.

“‘Well do you have a sister?’ I thought for a moment and I remember the bitch… (Sorry Mrs Capstick)… old cow and I sez, ‘Yes, captain.’

“And he says: ‘What would you do if you saw a Hun soldier taking liberties with your sister?’”

The table looked breathlessly at Gertie who made them wait.

“I sez: ‘I would try my hardest to interpose my body between them.’

“Any way, it didn’t work and now they’ve arranged it that I’ll be her batman now that she’s joined up. He’s going to beat the Germans by painting; can you believe it?”

“I don’t believe a fine fellow like you would be a shirker, Mr Gertie,” said Chilvers, ponderously. “I’m sure you love this country like we all do and like me can remember the dear old Queen.”

“Not too dear I hope Mr Chilvers— not on a servant’s wages. I suppose I was being a bit of a red ragger to the board. It must have been my hair. Do you like it?”

“It’s very fetching Mr Gertie,” said Miss Prims. “I can’t understand why someone like you is an unclaimed treasure.”

Gertie pursed his lips and looked at her hard, as if she were stupid, and said: “I could make you look like Marie Tempest if you let me do something with your hair. It’s a perfect fright.”

It was the following morning that a wagonette drew up in the slush. In it were Mr Destrombe, Dr Markby and a visitor. He was a young man, not very tall but with fine and sensitive features and an anxious expression. It was, of course, Hilaire Cuvelier, come to see his wife and new baby. Martin and Stephen welcomed him and without further ado ushered him up the stairs to where the dogs, still camped outside the door, sniffed him suspiciously and, deciding that he was all right, allowed him to pass.

The couple were allowed their privacy and Mr Destrombe and Chilvers supervised the unloading of the couples’ remaining possessions. The vicar spoke to the boys: “M. Cuvelier has obtained a position at Brunner-Mond in Winnington in Cheshire, my lord. I believe the company will provide him with a house. His expertise is in soda and nitrate production, which are apparently needed for explosives.” The vicar shook his head sadly.

“But they must stay here until they are quite ready to travel. They will need the support of the other Belgians too I should think,” said Martin.

Shortly after this, M. Cuvelier descended the wide, ancient, wooden staircase where once Queen Anne lightly trod and George IV had bellowed for a chamber pot. But no visitor was more distinguished than the carefully wrapped and rosy-pink bundle that was born by his proud, young father at this moment. Hilaire came over to Martin and thanked him for his hospitality and generosity, handing him the baby to nurse. Martin took the baby nervously. Then he approached Stephen with tears in his eyes and embraced him, planting a kiss on each cheek. They had chosen the name for their new son and it did not require many guesses to know what it would be.

And a very happy ending.

Dear Readers,

Henry and I would like to wish you all the best this Christmas Season and a safe and prosperous New Year. Thank you all for following our story.

We have also prepared a selection of photos from Lord Martin’s Scrapbook. If you would like to view them please send me an email @ pbruno@tickiestories.us and I will be happy to send you a PDF copy.

Posted: 12/20/13